Our approach to building the Agent Interaction SDK

By late last year it was clear that agents were improving rapidly. People were tweeting about them, prototyping with them, and sharing demos of newly derived, end-to-end agentic workflows. It seemed obvious that they were going to fundamentally change the way products are built. Instead of spending most of their time writing code, product teams were poised to reorient themselves around managing context and reviewing outputs.

We recognized that Linear was a good fit to become the orchestration layer where humans and agents interacted. Many teams did most of their product work in Linear already; agents just needed to meet them where they were. And, as a platform, Linear already had a strong foundation for third-party interaction: OAuth apps, scoped permissions, user roles, a rich API. The building blocks were there.

The work was figuring out how to bring agents into the system in a way that felt natural, adding only what was necessary. At the same time, we wanted to stay flexible. Developers were just starting to explore what agents could be, and we didn’t want to box them in.

We started thinking in terms of flexible guardrails—clear platform primitives and opt-in constraints that could guide behavior without limiting what agents were capable of now and in the future. Later we codified this thinking into our Agent Interaction Guidelines. Here’s how we got there.

Agents as first-class users

Before agents could participate in work, they needed to exist in the workspace. We already had a model for third-party apps—they could authenticate via OAuth and use the API to create issues, leave comments, and sync data—but these apps weren’t proper users. You couldn’t assign them work, mention them in a thread, or see what they were doing.

To enable that, we added a new actor mode to the OAuth flow: actor=app. When this actor mode is used, the app installation process creates a dedicated user to represent the agent inside the workspace. This dedicated user has their own OAuth token that is tied to specific scopes and teams that the agent can access. The scopes are requested by the agent’s developer, but the team access is determined by the user installing the agent into their workspace. The agent now has its own identity, token, and permissions within the workspace, all of which can be managed by workspace admins. Treating agents as first-class users follows a principle in our Agent Interaction Guidelines: an agent should inhabit the platform natively.

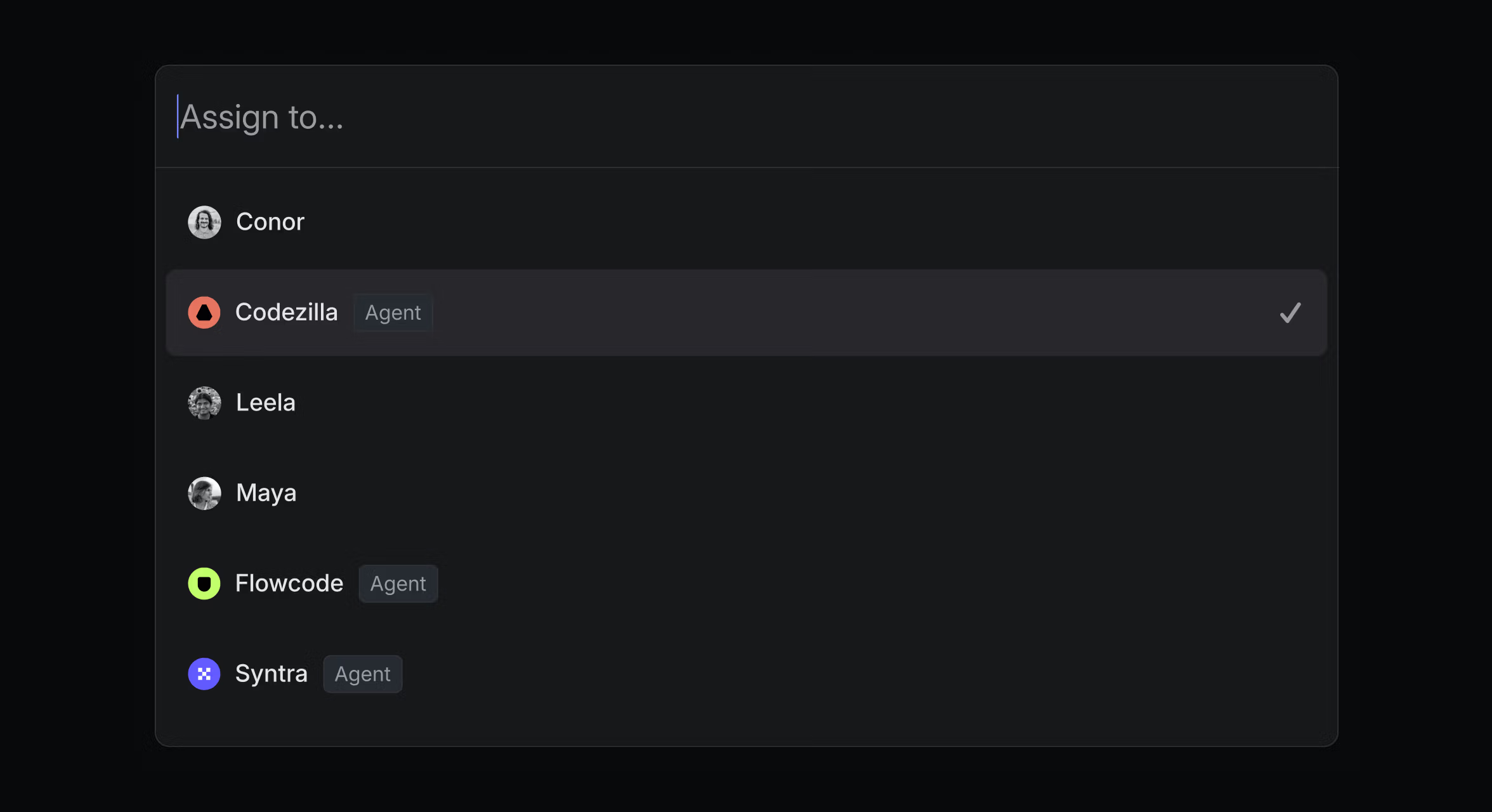

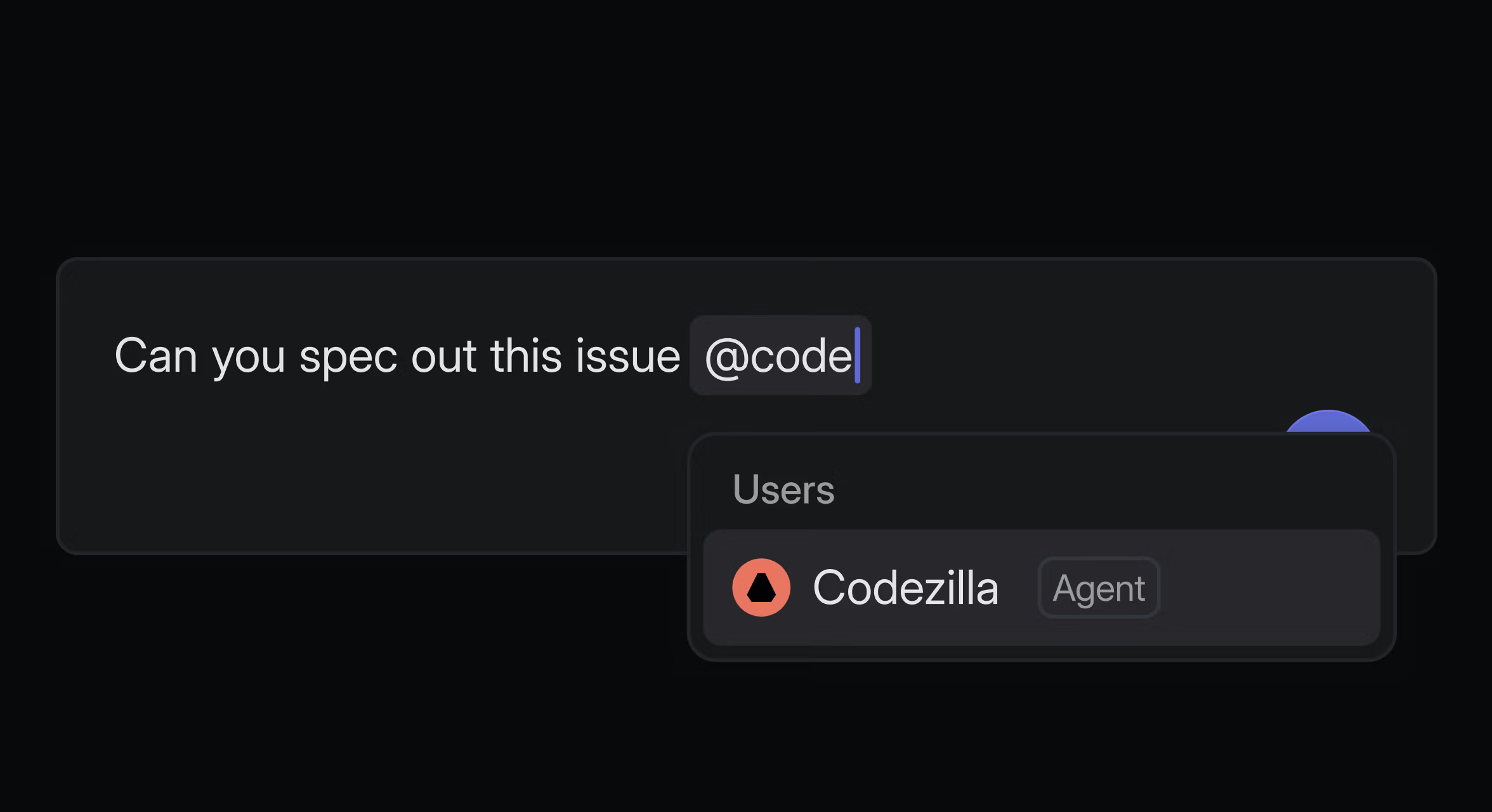

Once installed, they can show up in the assignee dropdown. They can be tagged in comments. You can click on their name and see what they’re working on. And because they’re clearly marked as agents—not people—the human-agent distinction is always visible. This aligns with another principle in our Agent Interaction Guidelines: agents should always disclose that they are agents.

Scoping agents’ work

Once we had a clean way to create agent identities, the next question was: What should they be able to do?

We wanted developers to be in control of whether their agent should appear in the assignment menu, or if their agent should be invokable through mentions. So we added two new scopes to the OAuth model: app:assignable and app:mentionable.

These scopes are opt-in. If you’re building an agent that should take on work—like getting assigned issues or tasks—you include app:assignable. If your agent needs to respond when mentioned in a comment or a document, you add app:mentionable. If you don’t include them, your agent won’t show up in those places. That made it easy to keep existing apps unchanged, and gave developers a clear way to opt into more interactive behaviors.

The nice thing about this model is that it sets you up to iterate. You might start with a low-touch app—one that listens for events or operates in the background—and later decide to make it more interactive. With these scopes, you don’t have to rebuild your app from scratch or worry about breaking anything for existing users. You just opt into the ones you need.

How agents listen

Once agents had identities and scopes, the next step was figuring out how they should listen. What should happen when an agent is assigned to an issue or mentioned in a thread? How does an agent know that it needs to do something?

Our first approach was straightforward. We already had a webhook delivery system and an inbox notification system, so we combined them. Since agents were now users in Linear, we mirrored a regular user’s inbox, just delivered via webhooks rather than inbox notifications or emails. If an agent was assignable or mentionable, we’d send a webhook any time it was tagged or assigned.

But that model pushed a lot of complexity onto the developer. You’d receive a notification webhook and have to figure out all the context around it: what the comment was about, whether the comment was in a thread, what issue it belonged to, and how to format your reply correctly. There were no patterns and no good defaults—some apps responded with an emoji, others with a new comment, and some didn’t respond at all. Even just replying to a comment took more code than it should have.

This lack of structure was intentional. We wanted to see what agents actually needed in the wild before codifying any abstractions. And now we have with "agent sessions."

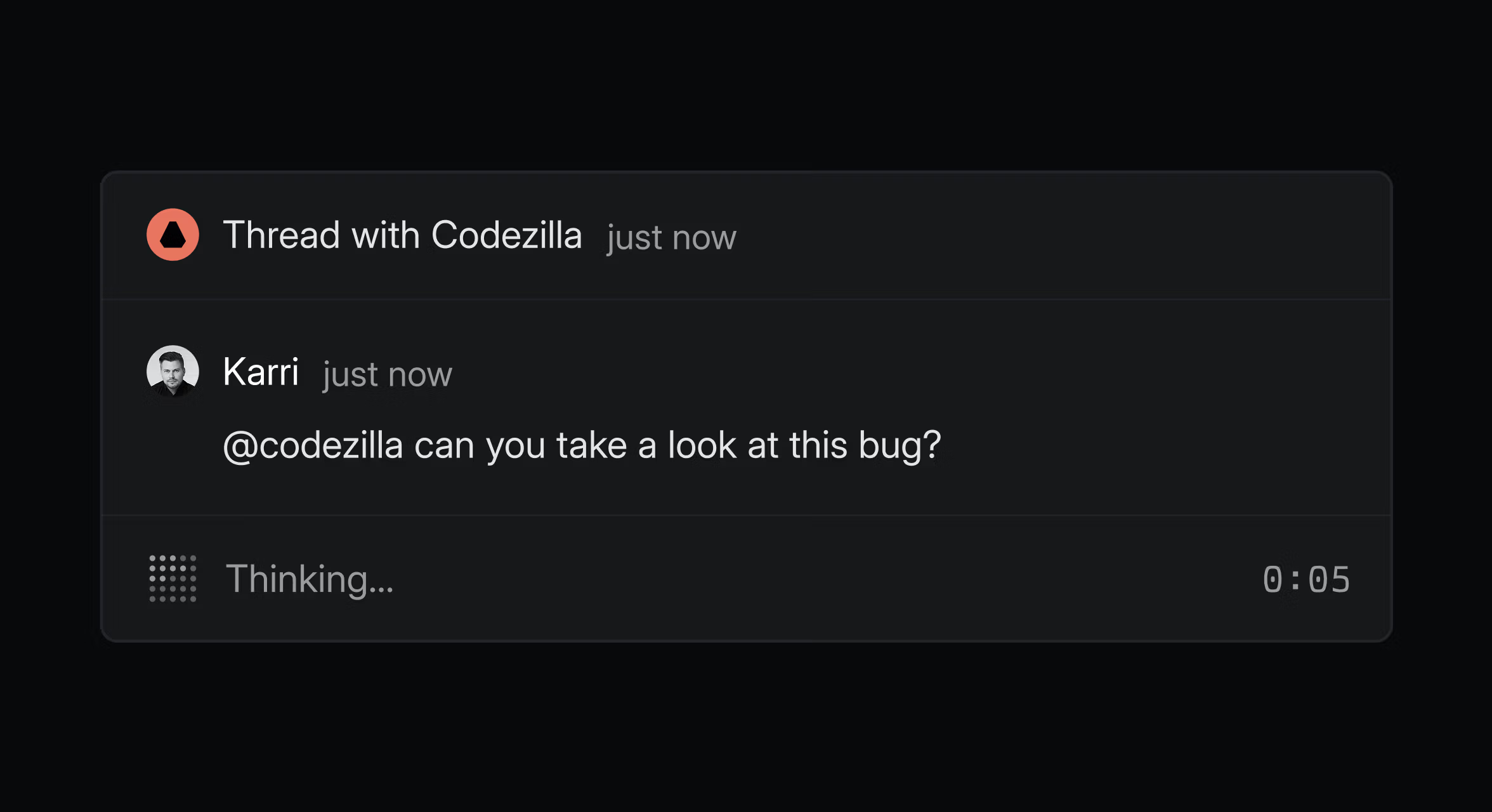

An agent session is an abstraction that represents the interaction between an agent and the Linear workspace, whether that’s an assignment, a mention, or some other trigger. When an agent session is created, we send a webhook with structured context: what happened, where it happened, who triggered it. Then the agent responds to the session directly, and we route that response to the right place in the product.

Agent sessions also track state. An agent can be waiting for input, actively working, completed, or errored. This gives us a way to manage the lifecycle of the interaction, and it gives users more visibility into what the agent is doing and why. We capture these ideas in two principles in our Agent Interaction Guidelines: an agent should provide instant feedback and an agent should be clear and transparent about its internal state.

The agent session model is part of how we’ve tried to strike a balance between structure and flexibility. We don’t tell you what kind of agent to build, or how it should respond, but we do give you a consistent surface for handling core interactions.

Delegating responsibility

One of the early questions we wrestled with was how to divide responsibility between agents and humans. You might assign an issue to an agent to see how far it can get. But unlike when you assign an issue to a human teammate, the responsibility doesn’t transfer. You’ll review the output, tweak it, maybe go back and forth with the agent, but you’re still the one accountable for the result.

We considered using sub-issues to model that relationship, but it didn’t quite fit. Sub-issues are intentionally independent, each with its own status and owner. We wanted tighter control over this human-agent responsibility loop.

That’s where the idea of “delegation” came in. Instead of assigning issues to agents as you would to human teammates, you delegate to them. This changes the shape of the assignment: the issue still has a human assignee—someone accountable for the result—but it also has a delegated agent responsible for taking action. It creates a clean taxonomy: issues can only be assigned to humans, and only delegated to agents. That reflects a core tenet of our Agent Interaction Guidelines: an agent cannot be held accountable.

The feature also helps with visibility. Before delegation, you’d sometimes see an agent with dozens of issues assigned, but no clear sense of who was behind them. If you disagreed with what the agent was doing, it wasn’t obvious who to talk to. Now, any issue involving an agent has both a human assignee and an agent it's been delegated to.

The future of agents in Linear

The current version of the Agent Interaction SDK provides a solid foundation but there’s still more to do, especially around helping agents share more of their thinking. Right now, most agents respond with a single comment or update. But as they take on more complex tasks, we want them to be able to explain what they’re doing and why. We’re already adding structured activity types—tool calls, thoughts, elicitations—that let agents surface their reasoning and make their behavior easier to follow.

We’ll keep evolving the platform, but with the same core ideas in mind. First, give developers the right set of primitives and guardrails to build agents that feel at home inside Linear. And second, stay flexible enough that our Agent Interaction SDK will work not just for the agents people are building today, but also for the ones no one has thought to build just yet.

Learn more about Linear for Agents.